The Way We Read Today

I don’t want you to react to this article.

I don’t want you to like it on Facebook or retweet it. I don’t want you to give it a quick scroll on your phone. I want you to do something really crazy: read it carefully and slowly. Maybe even come back to it later. And then, and only then, form a solid opinion on it.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the way we read these days, particularly as more and more people get their news and entertainment from social media platforms and less frequently from printed periodicals. In recent years, several studies have shown—including one I remember well from a Scientific American article I read in a waiting room back in 2013—that people reading on screens tend to read faster and don’t retain as much as they do when reading on good old-fashioned paper.

Part of it is the way we’re hardwired. We perceive the world spatially and often recall things based on their location. The reason why you remember that the passage you’re looking for is on the bottom left-hand corner of a page is the same reason why you always know to turn right at the red house on the corner. So an endlessly scrolling screen literally disorients us.

I’m not anti-tech. Sometimes it’s far easier to read something on a screen than on paper. Yet my concern about how we’re reading remains, not only because of the serious reading retention issues but also because of how we’re responding to our screen reading. These days we tend to scan headlines, read the most outrageous tweets, grow outraged ourselves. All of us react way too much, and too few of us take the time to develop informed opinions. Honestly, I have seen it far more than I like in my own behavior.

Unfortunately, many of our politicians take full advantage of this phenomenon. They were speaking in sound bites long before Twitter. They’re well- trained in knowing how to prompt a reaction, as if poking us with a stick. And we’ve become as well-trained as Pavlov’s proverbial salivating dogs in reacting.

Coupled with this issue is the fact that we’re confining ourselves to silo mentalities. We’re ever more unwilling to interact with anyone whose viewpoints might challenge our own. We scan our newsfeeds for like-minded people to back up our own quickly-formed opinions and feel satisfied when we find them. Nothing like that dopamine rush.

The great irony of our interconnected digital age is that we can connect to anyone, anywhere, at any time, but far too often we choose to talk to only the people who think exactly like we do. Or shout down those who we disagree with. And this is happening everywhere, both online and in real life, on college campuses and in workplaces. We no longer seem able to debate in an open-minded, impassive way or to give whomever we’re talking to the benefit of the doubt that they do not actually belong to a bizarre cult. I’m not just talking politics here. Try to discuss something like the recent Star Wars trilogy in a dispassionate way with uber-nerds like myself. I promise to burn your lightsaber-pierced corpse on a funeral pyre if you don’t make it.

Part of the issue has to be the speed of our culture. We can find out anything in an instant. Yet how often do we consider what we find carefully, in a broader context? Or even double-check our information to see if it’s accurate? So many of us almost never take the time to do more extensive research, either online or especially in books, to see if what we’ve found is actually true or if whatever opinion we’ve formed has validity outside of our own subgroup, whatever that subgroup happens to be.

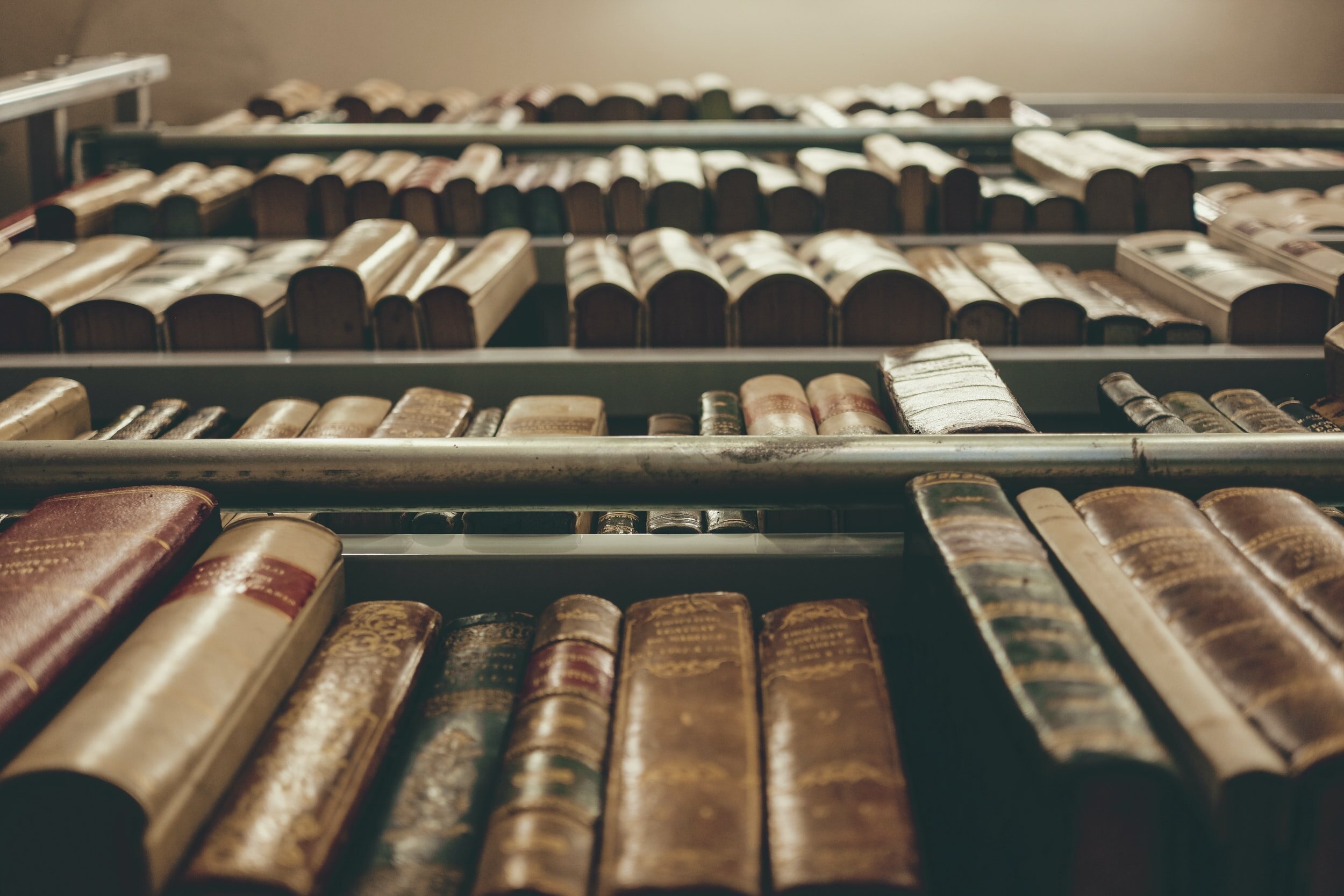

Then there’s the sheer amount of information we can access. We are gorged on information but starved for contemplation. All that easy information—wonderful as it is to anyone who remembers having to use a library card catalog—too often prevents us from going beyond the well-worn paths of our passions and out into the wider world.

The thing is, it wasn’t always like this. Once upon a time, people tended to read more broadly, if only through the benefit of browsing. They might, for example, read all of a newspaper’s opinion columns, gathering thoughts from intellectuals on the right, left and in the middle. Or they might discover a book they had never heard of just by perusing a bookstore or a library. They formed opinions from a variety of respected news sources and publishers. They listened to speeches by politicians who, in their best moments, didn’t talk down to citizens by appealing only to their base fears but who persuaded them with both soaring rhetoric and solid facts. When you’re done reading this, do a quick search for great speeches by FDR or Reagan, to take both sides of the political aisle, and compare them to what we’re hearing today.

So my concern is basically twofold. First, as a writer, I have skin in the game. I want all of us to think about what we read and see if it has meaning for our lives. I also believe that reading broadly shows how much more commonality there is to the human condition than the specific issues or experiences that separate us. The reason why Shakespeare continues to be read and performed is that his works appeal not just to the people of his time, but to all people, in all times.

Second, like just about everyone else out there, I want to see more positive and intelligent discourse in the political realm, and that means politicians should speak to more than just the subsets they believe will guarantee election victories. I’d love it if they would speak to everyone, and not just ignore groups they feel they can’t reach.

Yet, in the end, the really sad part about how we’re reading now is that we’re robbing ourselves of a really robust life. Honest discourse, the willingness to listen to divergent opinions, philosophies and ideas, the exchange of cultural traditions—these are all things that add to the richness and value of our lives. It’s what gives them flavor and makes them worth living.

If we don’t get out of our comfort zones, both online and in real life, we’re not going to grow very much as individuals or as a society. To continue my earlier clichés: we need to get out of our silos and off our beaten paths. That wandering in the open country, that time to reflect, to daydream and to warmly associate with all kinds of people is what in the end makes us fully human.

I’m not so cynical as to think we can’t change. I know we should. But it’s going to require a conscious effort on our parts to take the intelligence given to us and put it to its best use. That starts by doing something really radical: going offline now and then to give ourselves the time and space to really think about the world around us and all of the remarkable people in it.

So how do we prepare ourselves for this bold step? Maybe it’s as simple as just rediscovering our humility. In the grand scheme, we each know almost nothing. Yet, imagine how much we can learn from one another.

Christopher Mari is a freelance writer and novelist. He is the author of The Beachhead and coauthor of Ocean of Storms. His nonfiction has been published in America, Boing Boing, Current Biography, the Horn Book, the New York Daily News and Writer’s Digest, among other publications. Visit him at christophermari.com.